Abusing the CPU's adder circuits

by Gianni Tedesco

Have you ever been asked the interview question “how do you count the number of bits set in an integer?”

A smart-ass like myself might answer something like:

unsigned int count_set_bits(unsigned int x)

{

return __builtin_popcount(x);

}

Which, on x86_64, produces:

xor eax, eax

popcnt eax, edi

ret

The interviewer, of course, doesn’t like that. He wants to see you come up with an algorithm. So you come up with something like this:

unsigned int count_set_bits(uint32_t x)

{

unsigned int i, ret;

for(ret = i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

ret += !!(x & (1U << i));

}

return ret;

}

Which gives you something like:

xor r8d, r8d

xor eax, eax

mov ecx, 1

.p2align 4,,10

.p2align 3

.L4:

shlx edx, ecx, eax

test edx, edi

setne dl

movzx edx, dl

inc eax

add r8d, edx

cmp eax, 32

jne .L4

mov eax, r8d

ret

Which is, of course, dreadful. But the reason the interviewer likes this is because it sets up the next question: “how can we optimize this?” Or if you want to be more circumspect: “what if we only expect one or two bits to be set?” or “what if our data is very sparse?”

Realistically though, you either know about “Kernighan’s trick”, or, you don’t. It goes something like this:

unsigned int count_set_bits(unsigned int x)

{

unsigned int ret;

for(ret = 0; x; x &= (x - 1))

ret++;

return ret;

}

Which, at least for an Intel weenie such as myself, was a pointless exercise because gcc compiles that to:

xor eax, eax

popcnt eax, edi

mov edx, 0

test edi, edi

cmove eax, edx

ret

Which looks like a terrible code-generation bug in gcc. But hey, at least clang does the right thing here:

popcnt eax, edi

ret

Anyway, I digress. Did you notice the x &= (x - 1) part? That is bitwise

woo-woo magic to unset the rightmost bit in x. It’s a neat trick, and if you

know it you’ll ace this part of the job interview.

But later, when you’re at home, alone, contemplating the empty meaninglessness of the universe, you might ask yourself “but why does it work?”

Two’s complement

Let’s forget the & part and just focus on what x - 1 is doing for now.

One thing you’re going to need to know about is two’s complement arithmetic.

I won’t bore you by recapitulating the details but we should do well to remember the following equations:

\[\begin{align} x - y & = x + -y \\ -x & = \tilde x + 1 \\ \end{align}\]Therefore:

\[\begin{align} x - 1 & = x + -1 \\ &= x + 1111... \end{align}\]So the magic rune is just adding all one’s to our original value.

Half adder

So here’s the part where we get in to how addition really works. You probably have a good handle on this already from your school days, but let’s refresh.

The simplest case is if we’re just adding together a couple of 1-bit numbers.

Let’s write out the truth table for that:

| x | y | result |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0… oh yeah, we need to carry… |

Let’s try again:

| x | y | result | carry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Right, if we’re going to expand this to add numbers with more than one bit, we’re going to need to do something about this carry output.

Full adder

Let’s call the last adder with 2 inputs, and 2 outputs, the “half-adder.”

The full adder is going to have 3 inputs: the 2 operands, and then a carry-in which is going to be connected to the next least significant bit’s carry-out.

| x | y | carry-in | result | carry-out |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

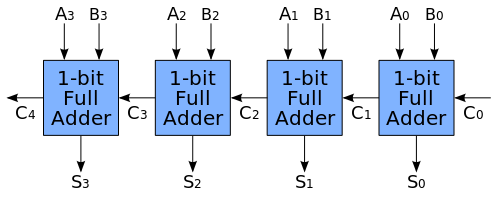

So you can see in this example of a 4-bit adder that there’s this chain of carry inputs going from right to left:

Thanks to Colin M.L. Burnett for the excellent diagram.

Putting it all together

The basic outline of the algorithm is that we start with an input, x. And as

long as it isn’t zero, we unset the least significant bit, and increment the

result.

So if the input is 1000_1100, the loop will iterate 3 times.

x &= (x - 1) is an operation which clears the least-significant set bit in

the input, x.

Since we’re going to do x &= mask, that must mean that mask has a zero in

the position we want to zero out. And it can’t have any zeroes where the input

has a one.

So we abuse the carry-chain to create such a mask. By adding 1111_1111 to the

input, we’re essentially ensuring that the carry signal is not asserted until

we hit the first one bit, but after that it will be asserted for all the rest

of the bits (travelling from right to left).

If we extract the relevant parts of the adder truth table we can see how the addition operation will produce the mask that we need:

| x | y | cin | result | cout | explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Before the first bit, produce ones |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | For the first bit, produce a zero and set the carry going |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | now the result is zero if x was 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | or 1 if x was one |

What that gives us is a number which is (from right to left):

- all ones (but that’s okay because corresponding input bits are zeroes)

- zero for the first one bit (which ensures that it will be cleared)

- and then equal to the input after that (leaving all higher bits unchanged)